Additional Analysis and Visualization#

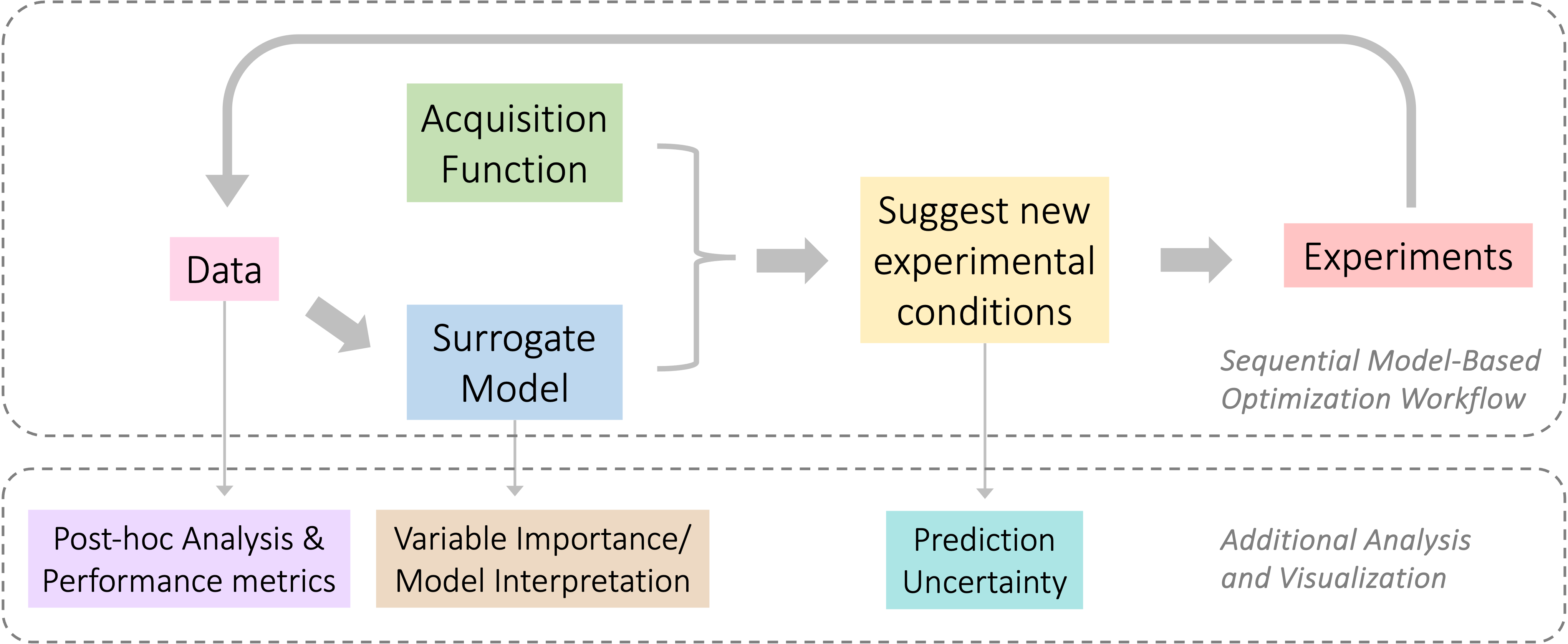

This section introduces some additional components, such as retrospective analysis and visualization methods, that are not essential steps in a Algorithmic Process Optimization (APO) algorithm but are valuable in real-world applications for several reasons.

The technical details involved in APO algorithms, such as surrogate models and acquisition functions, may seem complicated to users with non-quantitative background. As a result, the entire workflow of suggesting new experimental conditions may appear to be a black box for users, which hampers the adoption of this this powerful process optimization technique. Various performance metrics and model interpretation methods help to bridge this gap by providing users with a better intuitive understanding of the underlying algorithms and revealing the decision-making processes involved.

The variable importance analysis and/or model interpretation tools can provide critical insights into the optimization process, aiding in a deeper understanding of the variables that influenced the selection of optimal solution and the relationships between input variables, which could be confirmed with additional experiments or scientific domain experts.

Providing prediction uncertainty metrics along with the suggested candidates empowers practitioners to make informed decisions and establish realistic expectations of the surrogate model’s predictive performance and potential biases.

Please refer to submodule campaign for more details of analysis,

and submodule plotting folder for visualization utilities.

Post-hoc Data Analysis#

To simplify the description, assuming the preferred direction of any response variable is maximizing, and there are \(N\) data points collected for \(J\) experimental outcomes: \(\{ (X_i,Y_i) \}_{i=1}^N\).

If there are multiple experimental outcomes (\(J \geq 1\)), the \(j^{th}\) outcome in vector \(Y_i\) is denoted as \(Y_i^{j}\).

Evaluating the Measured Experimental Conditions#

A direct assessment of input features is assigning a binary indicator (True/False) to identify the best performer \(X_{opt}\) or an opimal solution set \(\chi_{opt}\).

Single-objective optimization: The best performer is the one (or more) inputs that achieve the optimal value of measured experimental outcome.

\[ X_{opt} = \underset{X_i, 1\leq i\leq N}{\text{argmax }} Y(X_i)\]Multi-objective optimization:

In some simple cases when the multiple responses \(Y^j (1 \leq j \leq J)\) are correlated, there may exist some best performer \(X_{opt}\) for all responses simutaneously:

\[ X_{opt} = \underset{1 \leq j \leq J}{\cap} \underset{X_i, 1\leq i\leq N}{\text{argmax }} Y^j(X_i) \]In most cases, there is trade-off between multiple responses and they cannot be optimized together. The Pareto Front (\(PF_Y\)) is the set of compromise solution, or nondominated solution, which are better than others in terms that improvement in any response \(Y_s\) comes only at the expense of making at least another response \(\{ Y_t \}_{t\neq s}\) worse:

\[\begin{align*} PF_Y = \{Y_i, i \in [1,N]: \{Y_w, w \in [1,N], w\neq i: Y_w^j > Y_i^j, \forall j \in [1,J] \} = \emptyset \} \end{align*}\]And the optimal solution set in feature space or Pareto optimal designs is the set:

\[\begin{gather*} \chi_{opt} = \{X_i, 1\leq i\leq N: Y_i \in PF_Y\} \end{gather*}\]

After multiple iterations, as the recommened candidates converge towards the best-performing or optimal solution set, multiple data points would exhibit near optimal measurements. However, due to the presence of experimental errors in measuring \(Y\), the aforementioned best performer set may not accurately optimize the unknown function \(f(X)\). Furthermore, minor deviations in the design space may not have a significant impact on the outcome values. Consequently, we are interested in expanding the the optimal set to include data points within its close neighborhood.

For single-objective optimization, the distance between the \(i^{th}\) outcome to the best performer \(\underset{1\leq i' \leq N}{\max Y_{i'}\}-Y_i\) can be used to rank the data points. For multi-objective optimization, the evaluation is subjective to user preference. Here are several common options to assign continuous score for each data point:

Its distance to the pareto front \(dist(Y_i, PF_Y)\). Various distrance metrics could be explored.

Its distance to an utopian point \(Y_U\), which is the desirable experimental outcome(s) specify by the user and doesn’t need to be feasible.

A weighted average across multiple outcomes \(\sum_{1\leq j \leq J} w^j * Y_i^j\) (weights are normalized: \(\sum_{1\leq j \leq J} w^j = 1, \forall w_j \geq 0\)), where the weights \(\{w^j\}_{1\leq j \leq J}\) are proportional to the subjective importance of each outcome. In this retrospective analysis, the weights could be different from the weights or formula used in defining the optimization objective.

The Overall Optimization Performance Metrics#

To monitor the progress of APO workflow, we need to define a scalar evaluation metric to summarize performance over all the \(N\) data points.

Single-objective optimization: The optimal value (either max or min, depends on target specification) of measured experimental outcome.

Multi-objective optimization:

Hypervolume: First define a reference point \(r_Y\) in the outcome space that serves as a baseline for evaluating the quality of measured outcomes, i.e. it defines the minimum acceptable value for each outcome. The reference point is often set as the lower bounds for each response. The hypervolume indicator metric \(HV\) is the volume of the space enclosed between the reference point \(r_Y\) and the Pareto front \(PF_Y\). It access the quality of a pareto front solution set: the larger the better. The space can be computed as the union of hyperrectangles bounded by each point in \(PF_Y\) and \(r_Y\) as vertices:

\[\begin{equation*} HV(\{Y_i\}_{i=1}^N, r_Y) = HV(PF_Y, r_Y) = Volume(\underset{y \in PF_Y}{\cup} [y,r_Y]) \end{equation*}\]Maximum weighted outcome: The maximum weighted outcomes \(\underset{1\leq i \leq N}{\text{max }} \sum_{1\leq j \leq J} w^j * Y_i^j\)

Minimum distance to the utopian point: \(\underset{1\leq i \leq N}{\text{min }} dist(Y_i,Y_U)\)

Surrogate Model Interpretation#

In this session, we assume the input feature \(X\) is a \(K\)-dimensional vector \((X_1, X_2, ..., X_K)\), and all the model explanation techniques are applied to each surrogate model outcome individually.

SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations)#

We use the Kernel SHAP algorithm to estimate the Shapley values, which is a feature attribution method that quantifies the contribution of each feature towards the surrogate model’s prediction for any input data, providing insights into variable importance and model explanation.

The Shapley value is a concept from game theory that aims to fairly allocate the total gains among the players in a coalitional game. In the original definition of the Shapley value, the contribution of each player is the difference in gains when including or excluding this player, averaged over all possible permutations of players. Let \(v(S)\) be the gain of any player subset \(S\), the Shapley value \(\varphi_k(v)\) for the \(k^{th}\) player is defined as:

It can be used to explain the outputs of a machine learning model, where the input features are considered as the players and model prediction is interpreted as the total gains achieved through the collaborative effort of these features.

Calculating the exact Shapley values is not feasible due to the large number of \(2^K\) possible subsets and the need to train a new prediction model for each possible subset of features for obtaining \(v(S)\). The Kernel SHAP algorithm implemented in SHAP package provides a model-agnostic and computationally efficient approach to estimate Shapley values.

Partial Dependence Plot#

Partial Dependence Plot (PDP) is a powerful visualization tool used in the interpretation and explanation of complex machine learning models. It helps to visualize the relationship between a specific feature and the target variable while holding all other features constant. PDPs are particularly valuable when working with sophisticated models like deep neural networks, random forests, and gradient boosting machines, which are often considered “black boxes” due to their complexity. By isolating the effect of a single feature, PDPs can reveal whether the relationship with the target variable is linear, monotonic, or more intricate. They also have the ability to uncover interactions between features, providing deeper insights into the model’s behavior. One of the key advantages of PDP is their relative ease of computation and interpretation, making them an effective means of communicating model insights to both technical and non-technical audiences. This versatility has made PDPs an essential technique in the field of explainable AI (XAI), allowing stakeholders to gain trust in and understanding of complex predictive models across various domains.

Individual Conditional Expectation#

Individual Conditional Expectation (ICE) plots serve as a powerful complement to Partial Dependence Plots (PDPs), offering a granular, instance-level perspective that reveals how predictions change for individual data points as a feature value varies, thereby uncovering heterogeneous effects and non-linear relationships that might be obscured in the aggregate view provided by PDPs. While Partial Dependence Plots (PDPs) provide a global view of a feature’s impact on model predictions, ICE plots offer a more granular, instance-level perspective. These plots illustrate how the prediction for a specific data point changes as the value of a particular feature is varied, while keeping all other features constant. This approach allows us to observe the model’s behavior at a local level, providing crucial insights into how the model makes predictions for individual instances. ICE plots are particularly valuable when dealing with complex, non-linear relationships or when there are significant interactions between features that might be obscured in aggregate visualizations. By displaying a separate line for each instance in the dataset, ICE plots can reveal heterogeneity in feature effects that might be averaged out in PDPs. This makes them especially useful for identifying subgroups within the data that may be affected differently by changes in a feature.

Sensitivity Analysis#

Sensitivity analysis around the optimal solution, particularly after the suggestions have stabilized over several iterations, serves as a critical step in validating and understanding the robustness of the identified solution. As the optimization process converges, it’s essential to examine how small perturbations in the input variables affect the output, ensuring that the algorithm hasn’t fallen into a local optimum or prematurely converged. This analysis helps quantify the trade-off between exploration and exploitation, a key consideration in Bayesian optimization. By systematically varying the parameters around the suggested optimal point, we can gauge the stability of the solution and identify any regions of high sensitivity. This process not only provides insights into the model’s behavior but also helps in assessing the reliability of the optimization results. Moreover, sensitivity analysis can reveal potential areas for further refinement or highlight the need for additional iterations if the optimal point proves to be unstable. In cases where the analysis indicates a robust optimal solution, it strengthens confidence in the APO outcome and provides valuable information about the parameter space surrounding the optimum. This understanding is particularly crucial in complex, high-dimensional problems where visualizing the entire optimization landscape may not be feasible.

Augmented Predictive Information for Candidates#

Prediction Uncertainty#

Adding prediction intervals as an uncertainty metric to suggested candidates is crucial for enhancing both the performance and interpretability of the optimization process. These intervals provide a quantifiable measure of uncertainty around predicted values, enabling a balanced approach between exploration of uncertain areas and exploitation of promising regions. This balance is key to avoiding premature convergence to local optima and making more informed decisions about where to sample next. Furthermore, they greatly enhance the explainability of the process by visually and numerically representing the model’s confidence across the parameter space. This additional context allows for clearer communication of potential risks and rewards associated with different candidate points. By incorporating prediction intervals, APO becomes a more transparent and interpretable tool, which is crucial for its effective real-world applications where understanding the rationale behind suggestions is as important as the suggestions themselves.

Miscellaneous#

(TBA…)